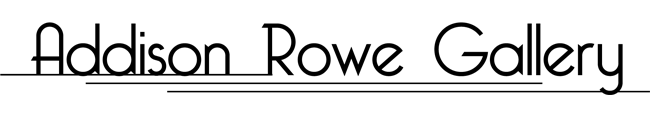

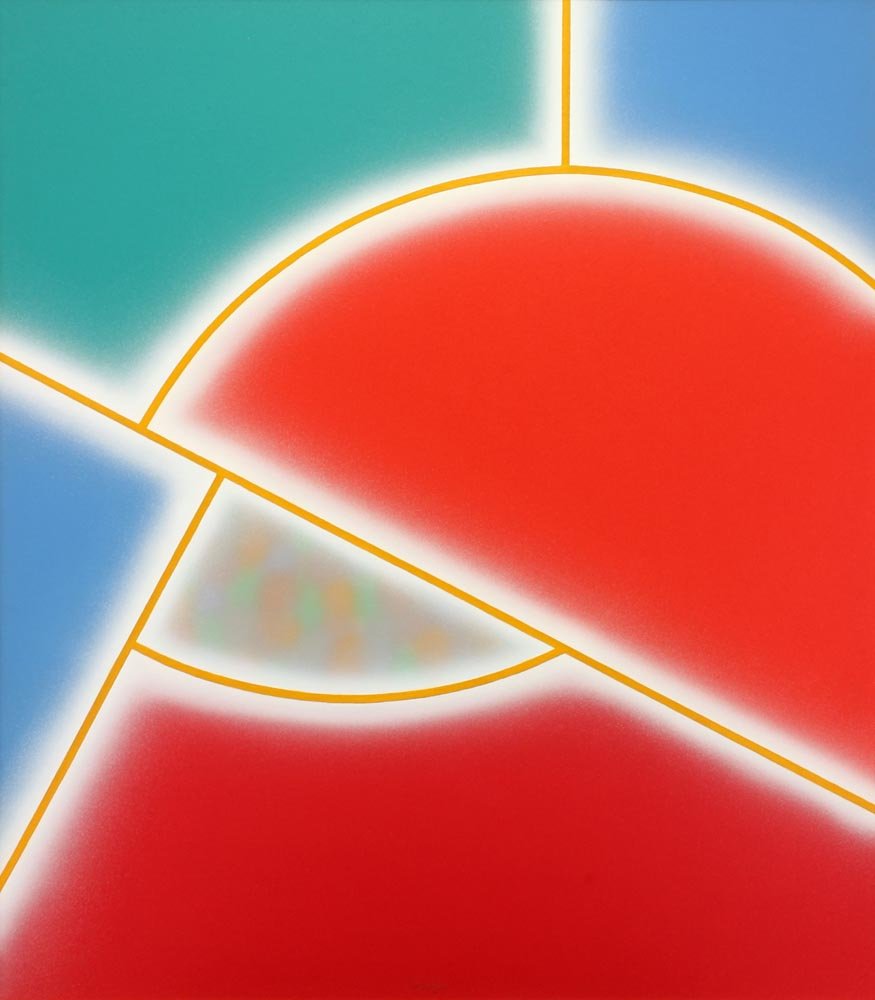

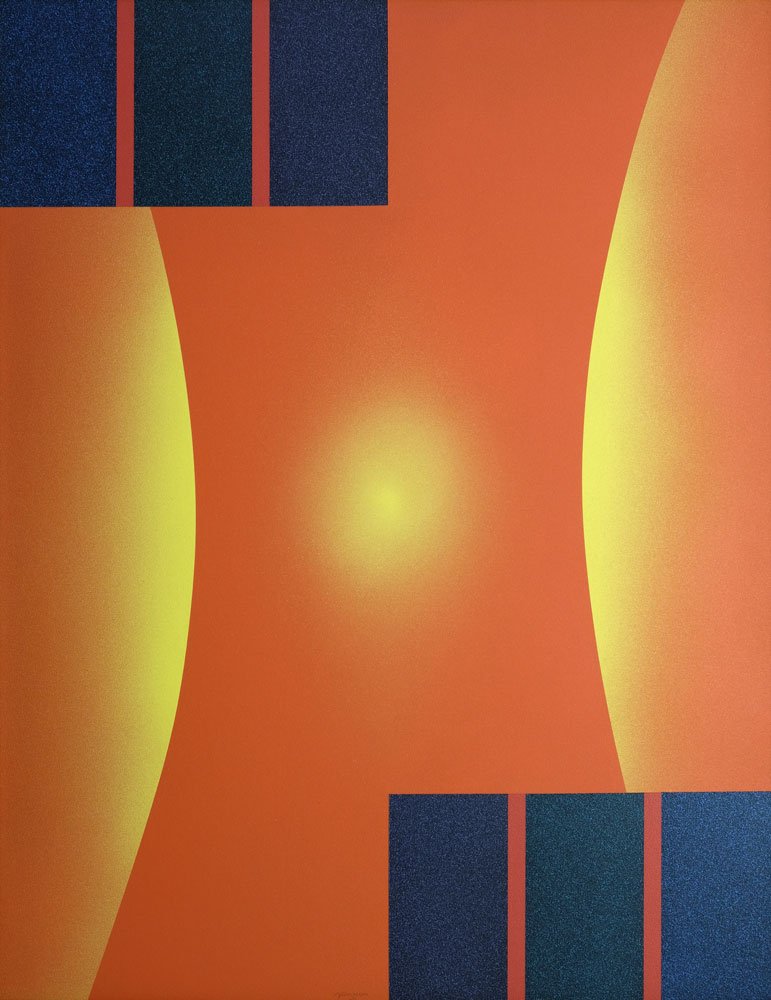

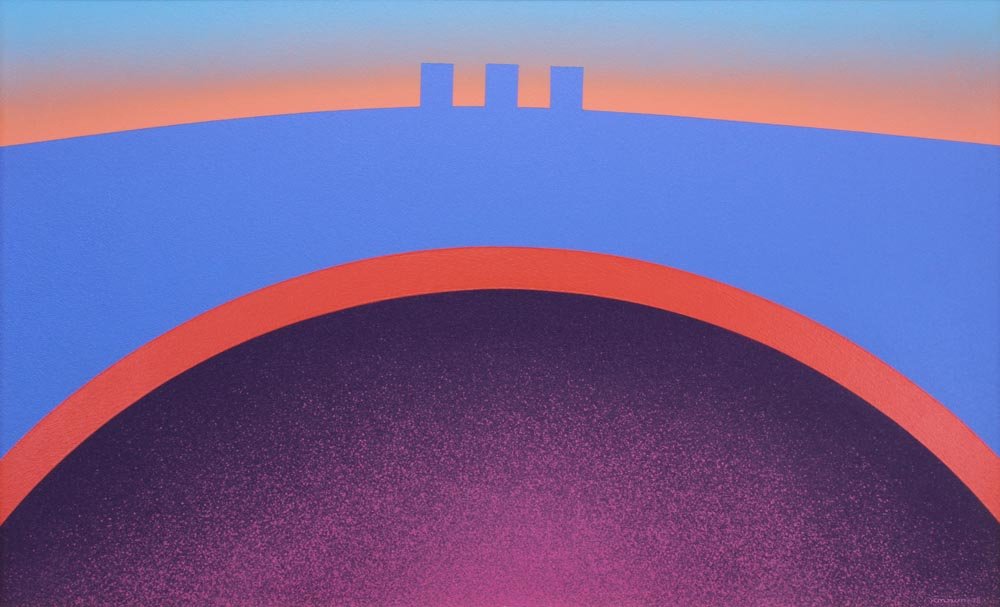

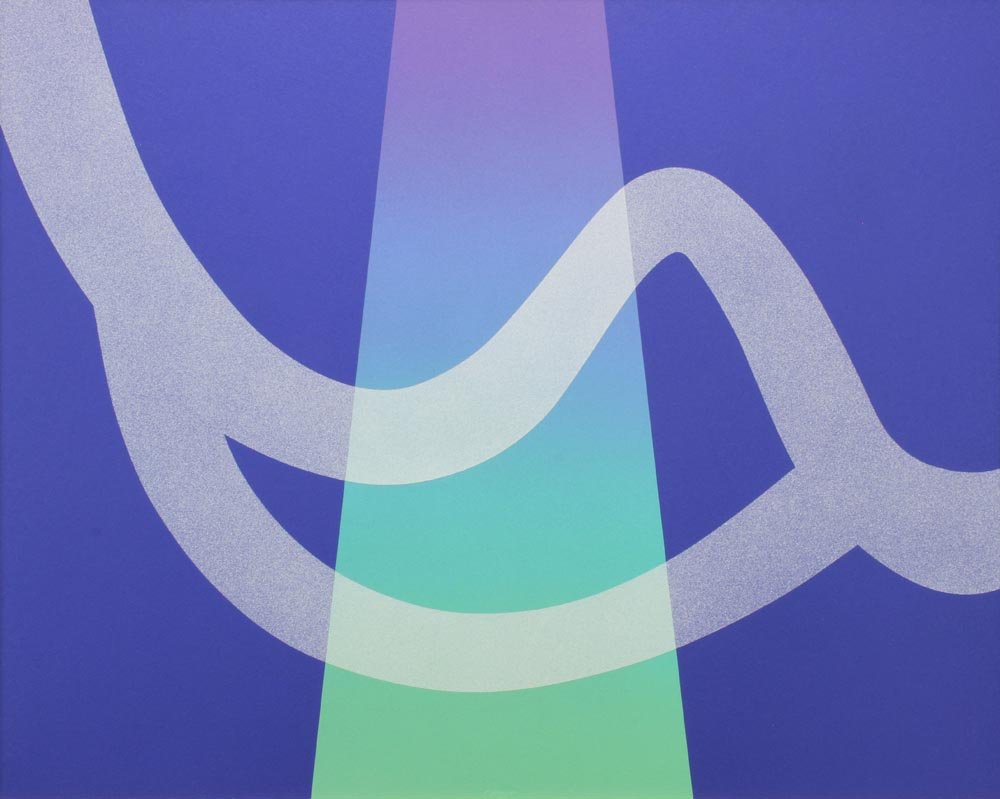

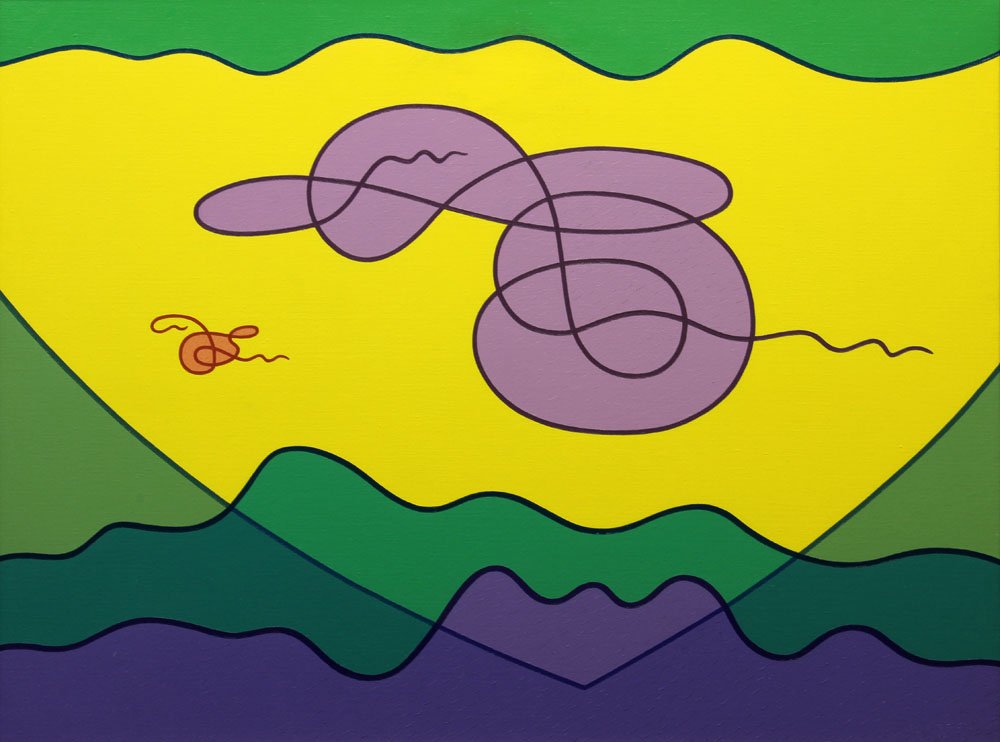

Image Source: UNM ART MUSEUMRAYMOND JONSON

1891-1982

Represented by Addison Rowe Gallery in Santa Fe, NM, Raymond Jonson was one of the foremost 20th century nonobjective painters in America. Although his celebrity was not that of other painters who traveled to New Mexico, such as Georgia O’Keeffe or Marsden Hartley, his contributions to art were on par with the most celebrated Modern artists.

He founded many artist groups in both Chicago and New Mexico, including the Transcendental Painting Group and Cor Ardens. Greatly influenced by Wassily Kandinsky and the Bauhaus artists, he advanced new technologies in American art (e.g. the use of the airbrush and polymer paints), and devoted himself to exploring the spiritual in art.

RAYMOND JONSON BIOGRAPHY

-

Raymond Jonson was one of the foremost 20th century nonobjective painters in America. Although his celebrity was not that of other painters who traveled to New Mexico, such as Georgia O’Keeffe or Marsden Hartley, his contributions to art were on par with the most celebrated Modern artists. He founded many artist groups in both Chicago and New Mexico, including the Transcendental Painting Group and Cor Ardens. Greatly influenced by Wassily Kandinsky and the Bauhaus artists, he advanced new technologies in American art (e.g. the use of the airbrush and polymer paints), and devoted himself to exploring the spiritual in art. The Jonson Gallery, founded in the 1950, was a permanent exhibition space dedicated to the progression and exhibition of spiritual-nonobjective art. It was not solely Raymond Jonson’s art which made him noteworthy, but his contributions to Art as an innovator, teacher, curator, and mentor.

Raymond Jonson was born Carl Raymond Johnson on July 18th, 1891 in Chariton Iowa. Both his parents were Swedish immigrants, and his father, Gustav, was a reverend in the Baptist church. Gustav’s duties to the church required the family to relocate often (Raymond was the eldest of six). Raymond grew up all over the American west and was intimately familiar with the landscape. Raymond’s mother taught him to read and write; he did not attend school until 1899 when his family lived in Colorado Springs, Colorado. In 1902, his family settled permanently in Portland, Oregon (Hartel 20).

Johnson showed an interest in the arts from an early age. He was the first student to register for classes at the Portland Art Association School of Art when it opened in 1909. In 1910, at the age of nineteen, Jonson moved to Chicago to continue his art training at the Chicago Academy of Fine arts. During the two years he attended, he received formal art training in composition, color theory, anatomy, drawing from a nude model, oil painting, and commercial design and illustration (Hartel 29). In 1911, Jonson met B.J.O. Nordfeldt who was a teacher at the Academy. Nordfeldt was a mentor and friend to Jonson for the rest of his life and was responsible for converting Jonson to modernist modes of visual expression (Hartel 38; Garman 14).

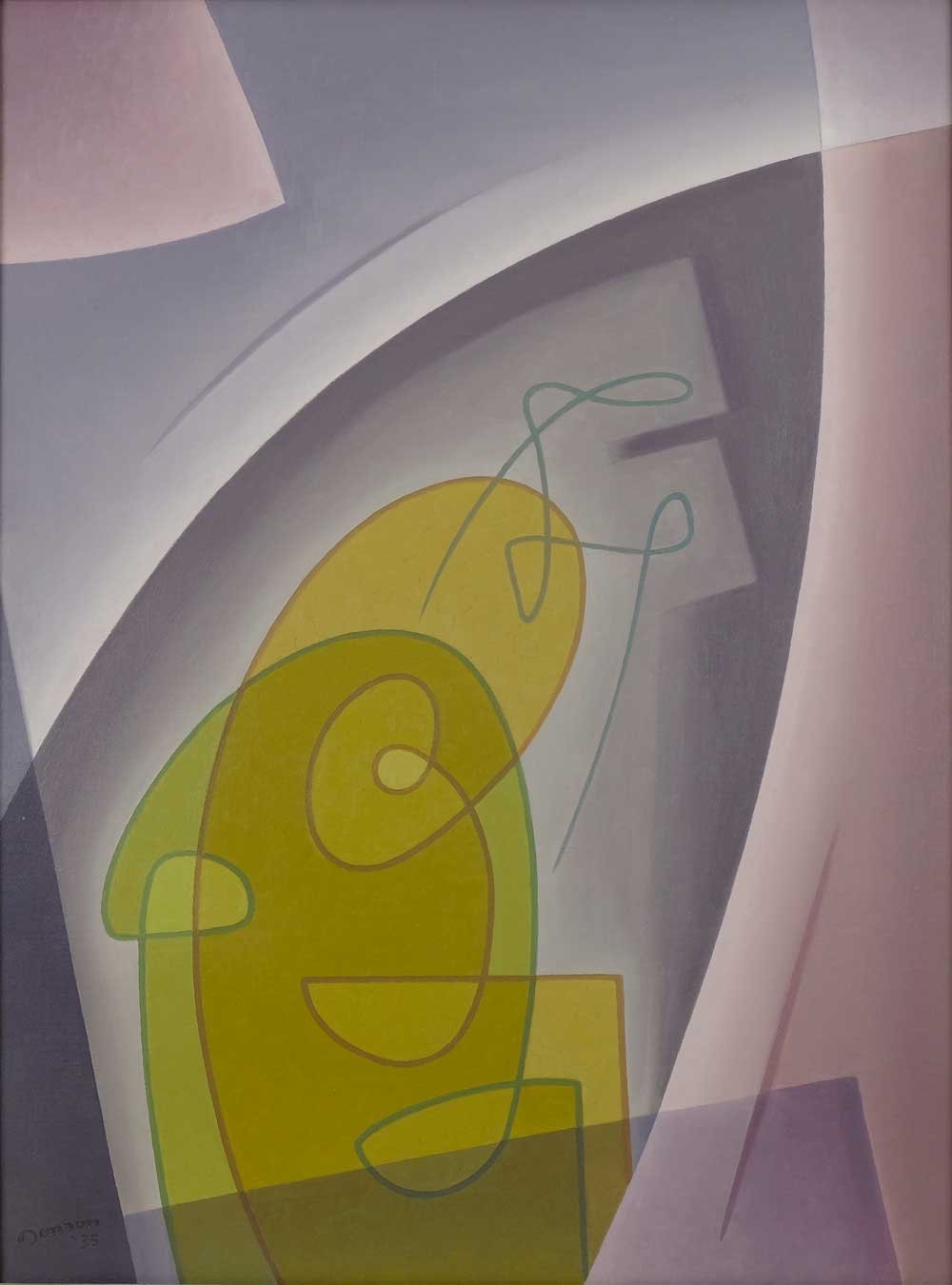

1913 was a seminal year for Jonson. He viewed the Armory Show the day it opened in Chicago—it left him feeling that, “artists could now make paintings that freely express their temperament, ideas, and views of the world, and their experiences of the physical reality around them” (Hartel 48). In the same year, he had his first public art exhibition at Third Annual Exhibit of Swedish-American Artists at the Swedish Club in Chicago. There he met Swedish-American painter Birger Sandzén, who became a lifelong friend and mentor (Hartel 78, 91). Also in 1913, Jonson began working at the Chicago Little Theatre. Hired upon the recommendation of Nordfeldt, his duties included stage-designer, stage-manager, stage-carpenter, scene-painter, sceneshifter, electrician, and, on occasion, actor (Garman 26). He worked at the theatre until it closed in 1917. In 1916, Jonson met Vera White, an amateur musician who worked for the Chicago Little Theatre as a secretary. The two married on December 25, 1916 (Hartel 30).

In 1920, Jonson (spelled Johnson at the time) looked through a Chicago phonebook and realized his exact name was only one of many. As an emerging artist, he wanted a way to distinguish himself, yet not dissolve ties to his family and past (Ware interview). When his father immigrated to the United States, he changed his surname from the Swedish Jonsson to the Americanized Johnson. Raymond settled on Jonson [pronounced JOAN-sen] to blend his need for individuality with his past (Hartel 20).

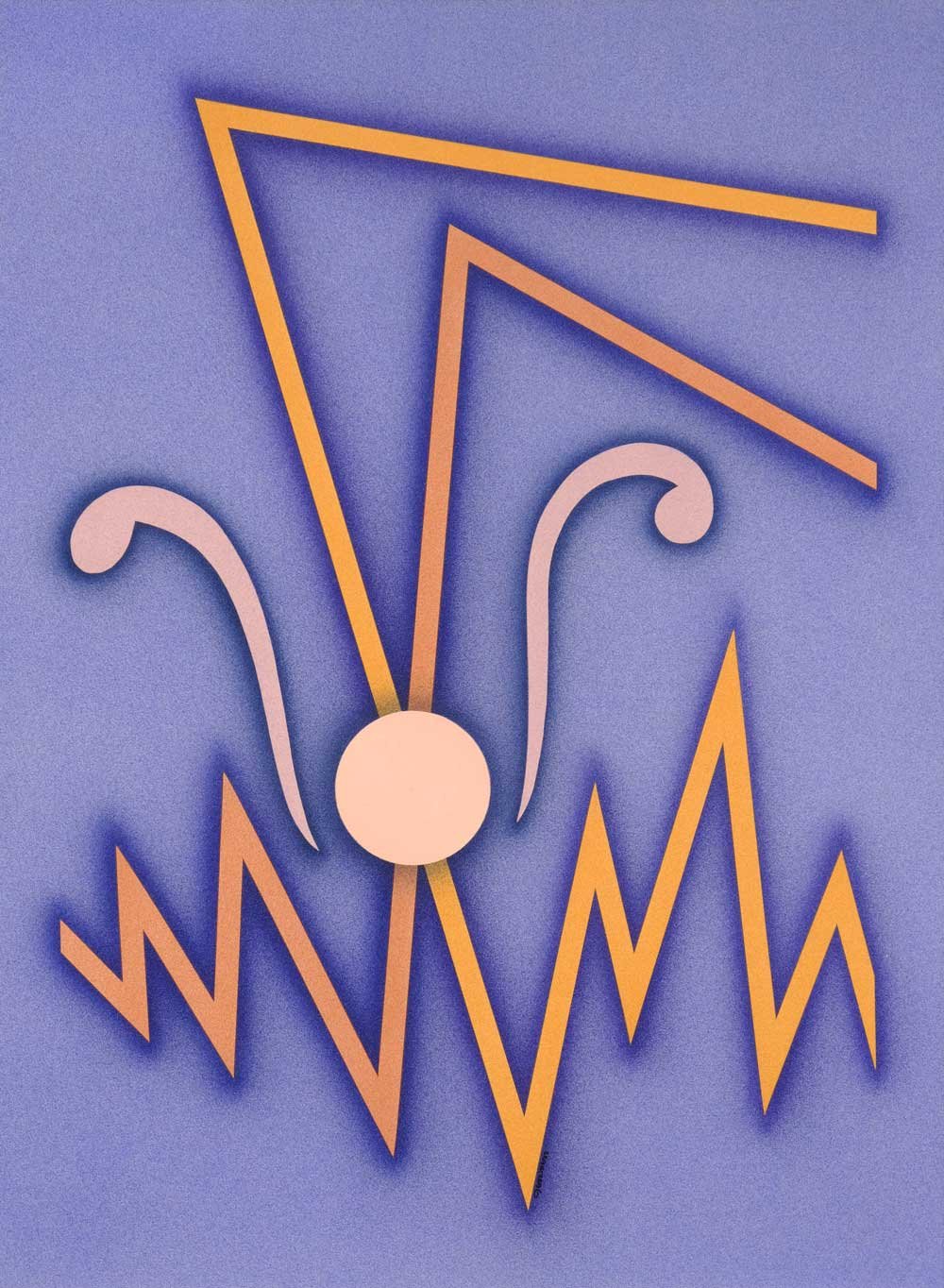

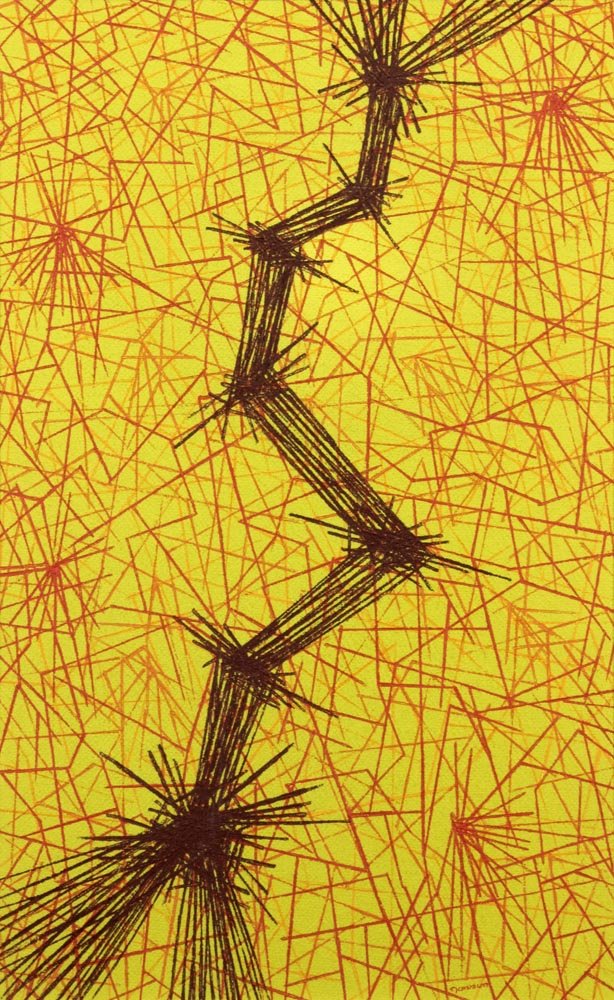

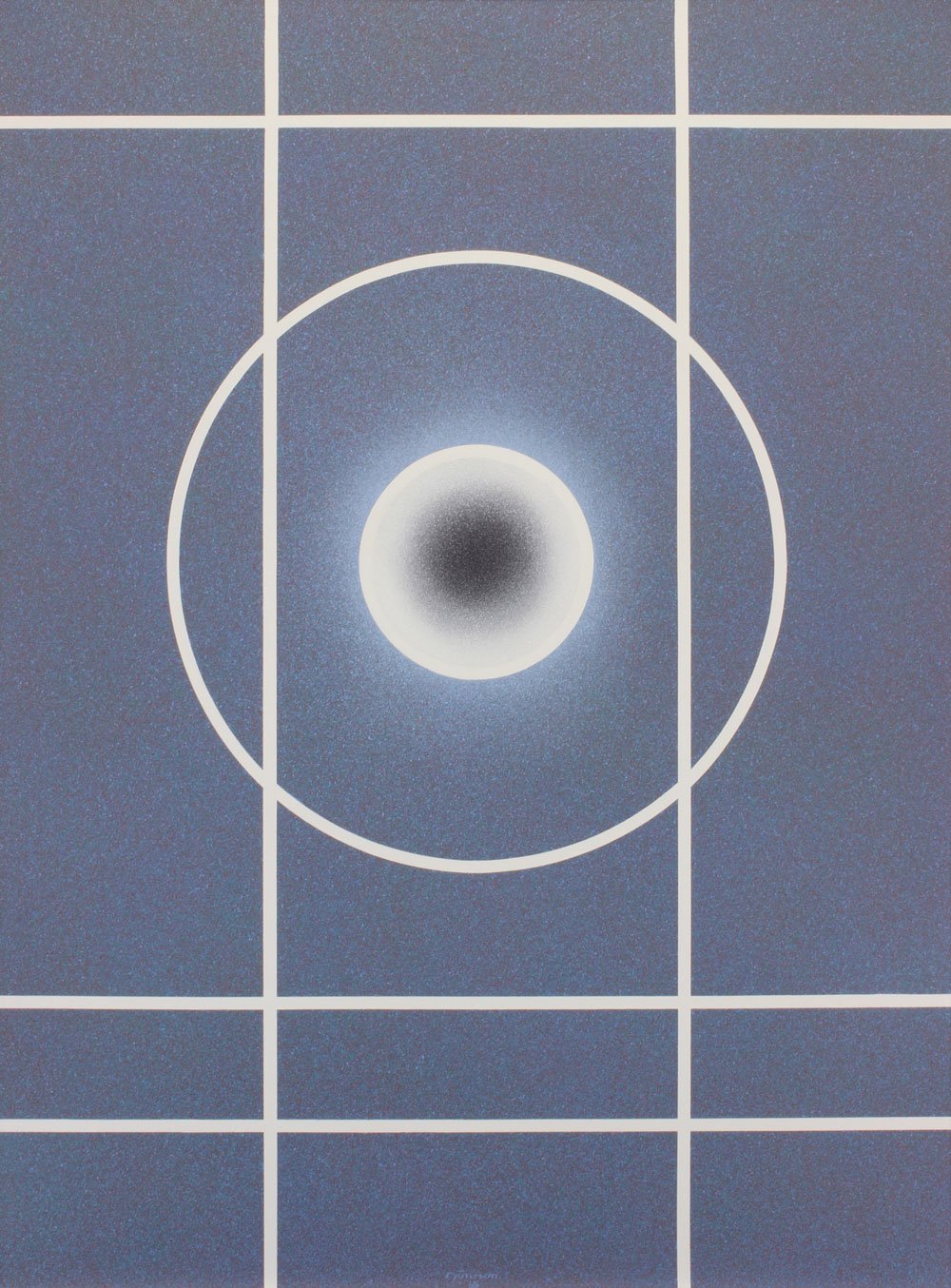

Jonson received a copy of Kandinsky’s The Art of Spiritual Harmony in August of 1921. He first viewed works by Kandinsky in 1913 at the Armory show, and the book confirmed many thoughts that he had developed independently. Foremost was Jonson’s fundamental belief that art was a spiritual endeavor and that paintings should be an expression of the spirit. Additionally, Jonson thought of himself as akin to a musician—his wife, brother, sister-in-law, and brother-in-law were all musicians. While working at the Chicago Little Theatre, he manipulated the light for plays as a composer would musical notes (Ware 33). He transferred this concept into his paintings—color wasn’t a stagnant and transparent detail, but a physical object with its own weight and presence: “Some of us want to do the same thing with color, line, and shape that a musician can do with sound. We want to compose independent of imitation and to express in plastic form the inner significance of vibrations and a certain sense of cosmic rightness through the functioning of intellect and the subconscious” (Garman 105). The influence of Kandinsky is evident through the rest of Jonson’s career.

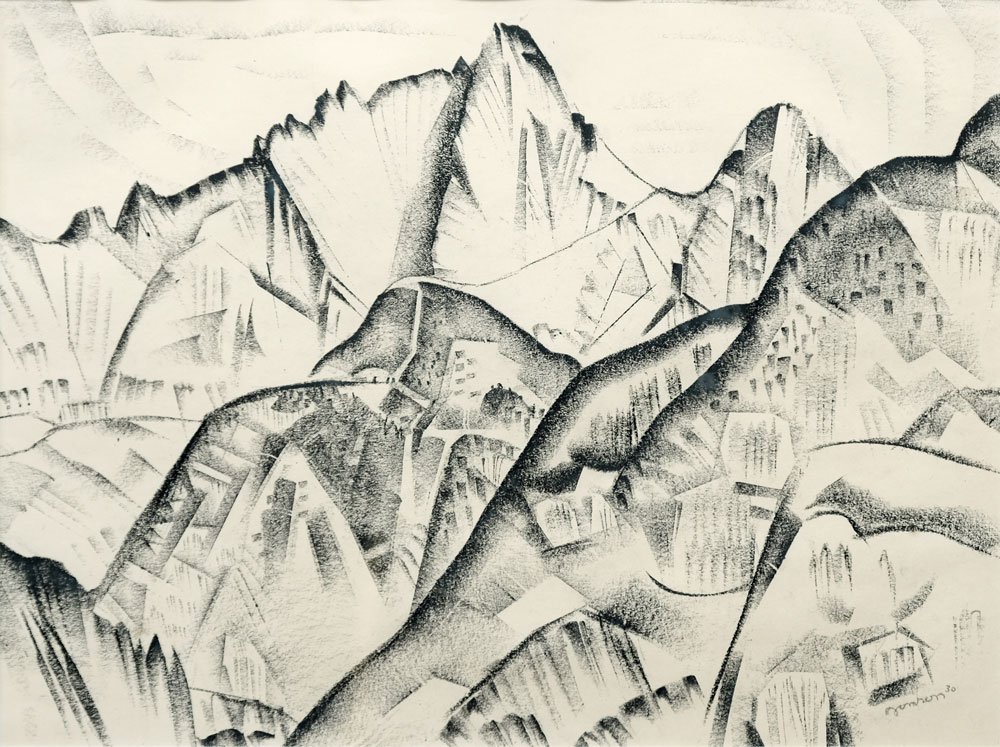

At the encouragement of Berger Sandzén, Jonson and Vera spent the summer of 1922 in New Mexico. Although this was not his first visit to the state, it was far more influential than his first—inspiring him to change the direction of his life and art. It was during this trip that he decided to relocate to New Mexico. He painted only sporadically over the next two years, focusing his energy on making enough money to pay his debts in Chicago and move to Santa Fe. The aesthetic beauty of the Southwest did not solely inspire his decision to relocate; it was the need to live inexpensively and to escape the noise, dirt, and hectic pace of the modern American city, which was more often than not unappealing to Jonson (Hartel 86).

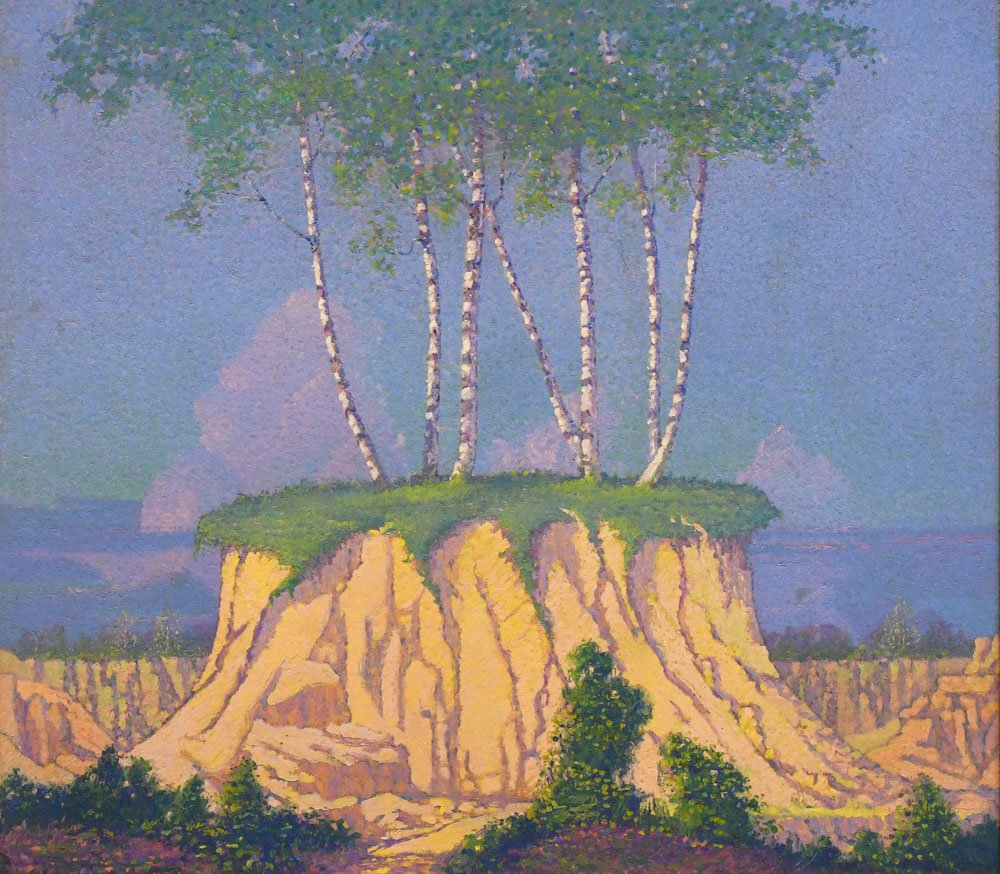

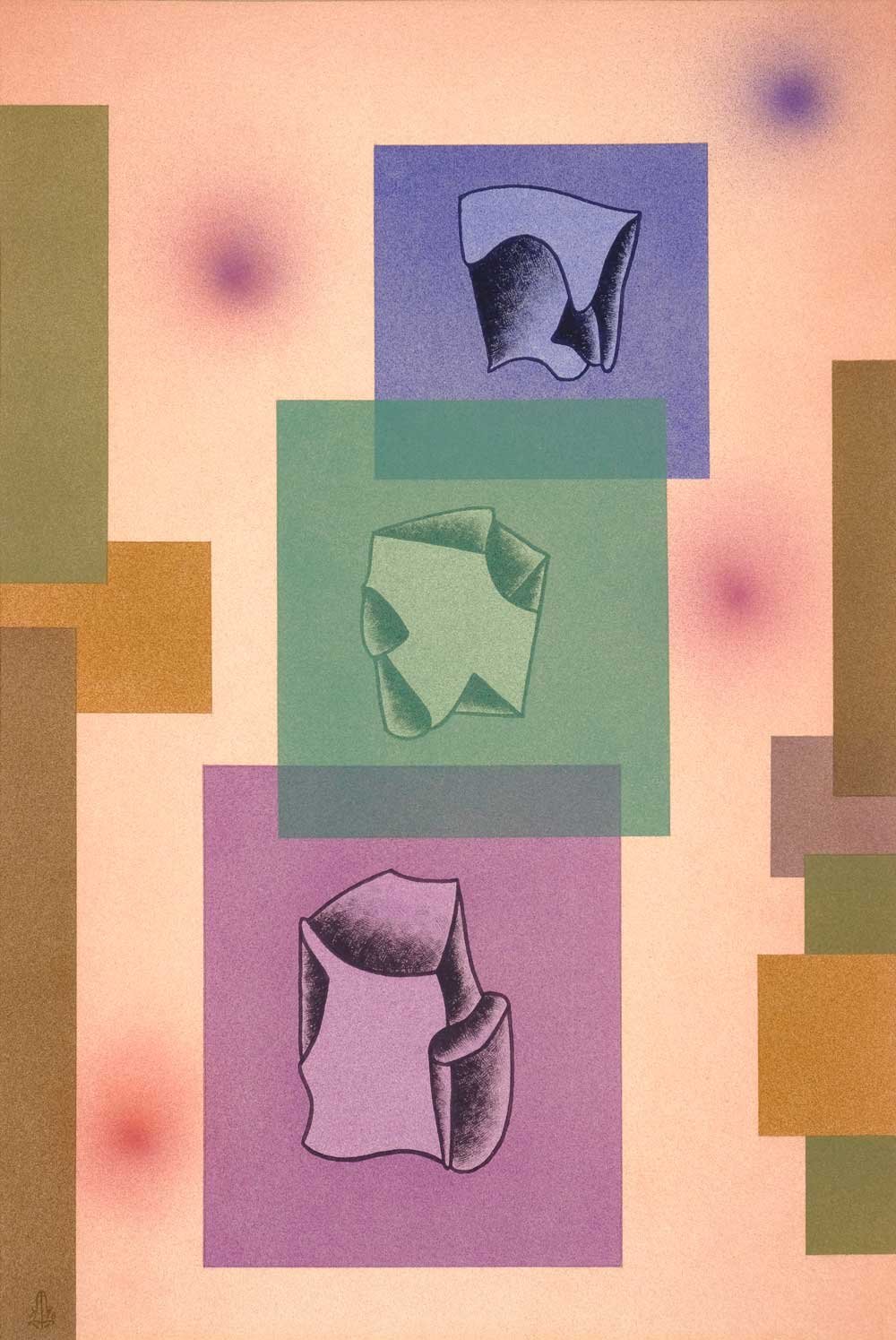

Upon arriving in Santa Fe in 1924, Jonson and Vera were able to purchase two and a quarter acres of land off of the old Santa Fe Trail for $460 (Hartel 96). However, the move did little to alleviate Jonson’s financial problems—he earned just enough to survive by teaching art and selling art supplies from his garage. In 1927, Jonson formed the loose-knit group of artists named “Six Men.” This consisted of Jonson, Nordfeldt, Andrew Dasburg, Jozef Bakos, Willard Nash, and John E. Thompson. They exhibited together in Seattle, Tucson, and San Francisco. In 1929, Jonson abruptly changed his subject matter, almost entirely giving up landscape painting, which was his primary expression up to this point. Instead, he adopted highly abstract images of plant forms, numerals, alphabet letters, colors, and modern architecture (Hartel 161). This was a major step toward depicting the spiritual world and transcending the physical. In early 1934, Jonson began teaching at the University of New Mexico. He took over the teaching assignments of Kenneth Adams, who moved to Europe for a year. Although at first he only taught once a week, this position would be the keystone that changed Jonson’s life (Hartel 96 -100).

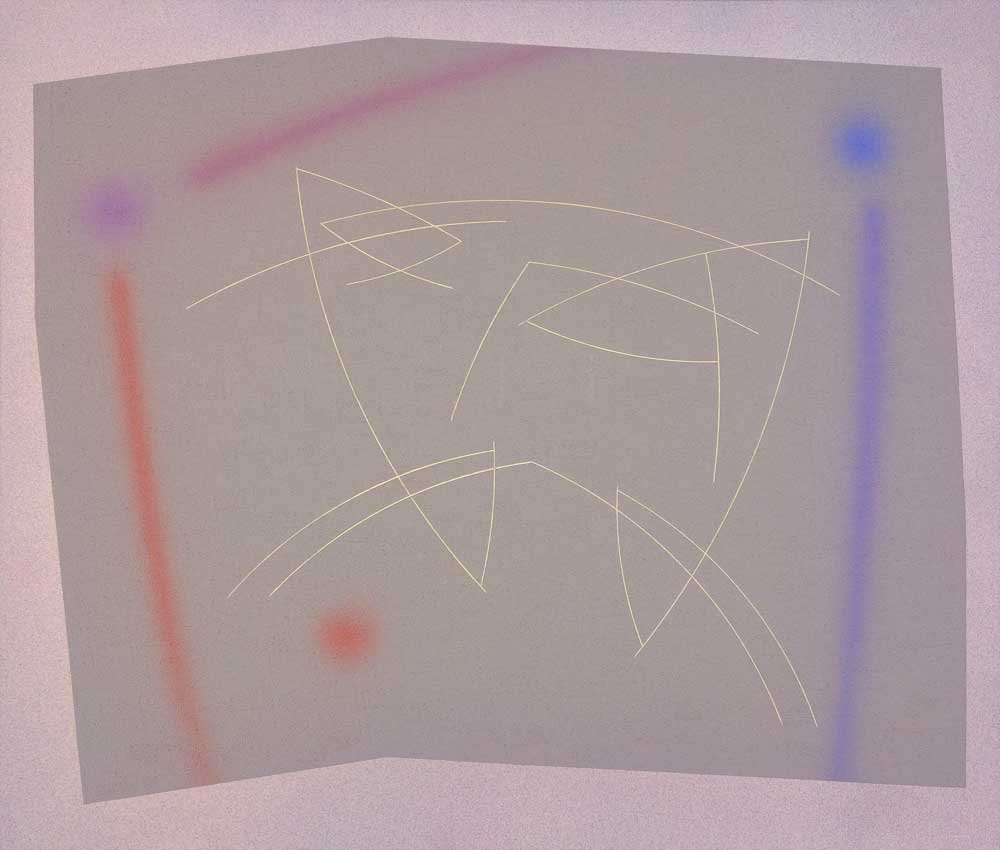

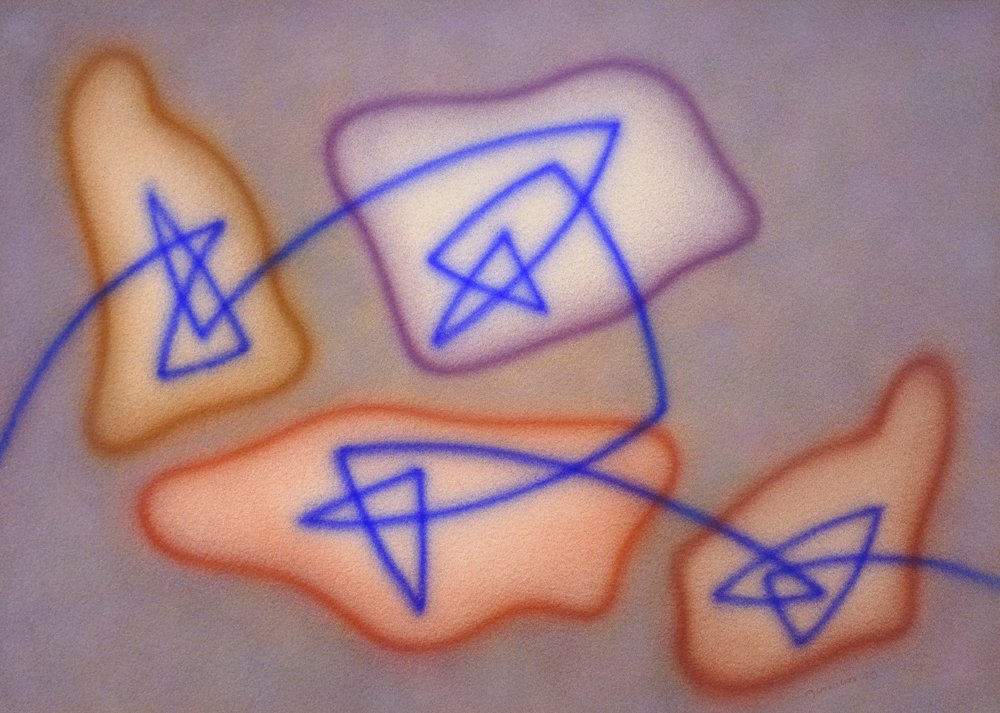

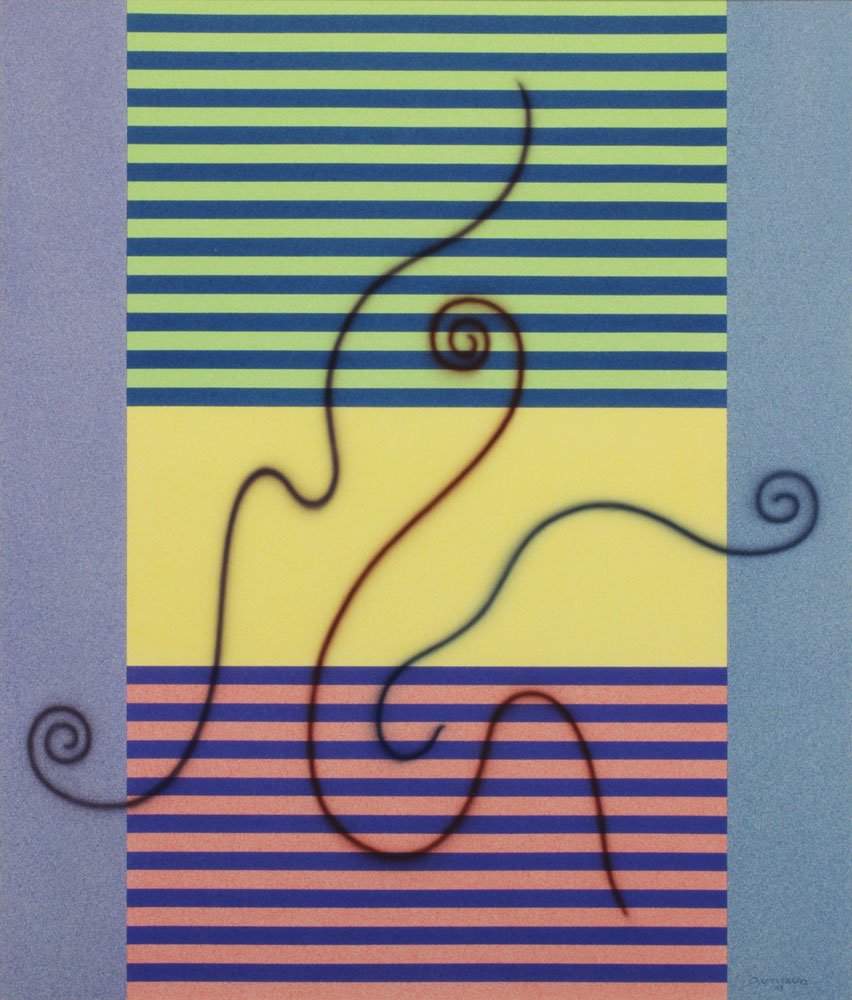

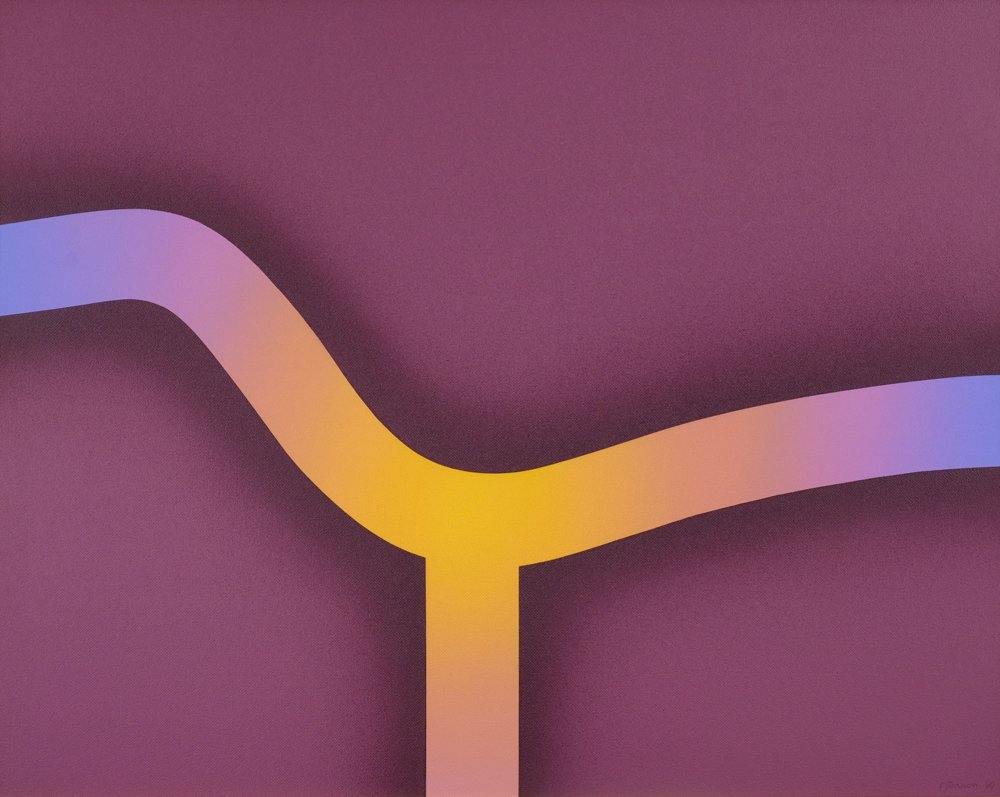

Jonson’s work went through another profound change in the late 1930s. This was due to two important factors. The first was his meeting Lazlo Moholy-Nagy in Chicago in late 1937 and the second was the founding of the Transcendental Painting Group in 1938. Jonson wrote little about Nagy, however, meeting one of the members of the original Bauhaus and a peer of Kandinsky was undoubtedly deeply inspiring. One aspect of this influence is evidenced in Jonson’s method of naming his work. From this point on, he titled all his works according to medium, number, and year (e.g. Watercolor No. 1, 1940). Moholy also avoided using descriptive titles and preferred to name his work Construction or Composition with an associated number. The Bauhaus artists also employed the airbrush and, in 1938, Jonson began using it regularly. The airbrush was a stylistic and expressive epiphany for Jonson. It allowed him to apply paint quickly and efficiently while also focusing solely on form and color without the physical intervention of a brush. It was a merger of medium and message (Hartel 262, 268, 272-273, 286).

In 1938, Raymond Jonson and Emil Bisttram founded of the Transcendental Painting Group (TPG). Although small and short lived, the TPG reflected a growing desire in artists to express one’s inner thoughts, emotions, and spirituality in an abstract manner. It was analogous to the American Abstract Artists (AAA) that began in New York in 1936. It is important to note that throughout the great depression and World War II, people viewed abstract art as a luxury. The overall trend in art was toward Regionalism and Social Realism. For any group of artists to disregard this trend in favor of abstraction was to attract public derision. The TPG was a validating force in Jonson’s new artistic developments—he was not the only artist at the time focused on abstraction and spiritually. The TPG consisted of: Raymond Jonson, Emil Bisttram, Agnes Pelton, Lawren Harris, Florence Miller Pierce, Horace Towner Pierce, William Lumpkins, Robert Gribbroek, Stuart Walker, and later Ed Garman (Dane Rudhyar was an affiliated member). They sought to disassociate themselves from the Transcendentalists of the Transcendental Movement in American Literature. However, they could think of no better word to describe their goals—they transcended the politics of art and society, the petty squabbles of mankind, and created art purely for the purpose of making the world a more beautiful and harmonious place in which to live. In this endeavor, they believed that abstract art could more clearly express sensations of beauty and harmony than artwork that referenced society or nature (Ware interview). At the beginning of World War II, many of the members of the group were drafted and thus began the slow decline of the TPG. By 1945, only a few members were still paying their dues and the TPG officially disbanded, although the group had functionally ceased to exist in 1942 (Hartel 251, 252, 259, 263).

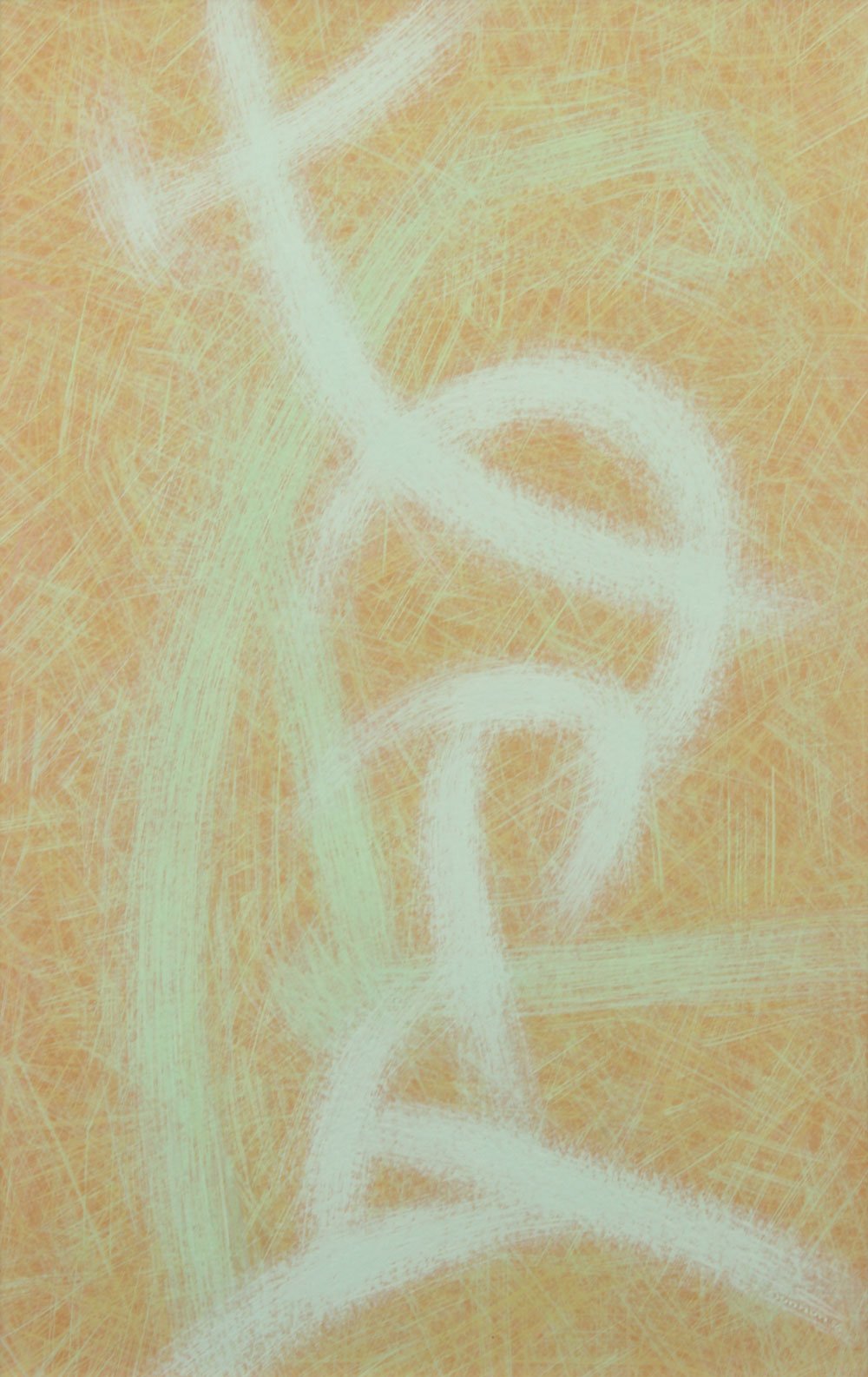

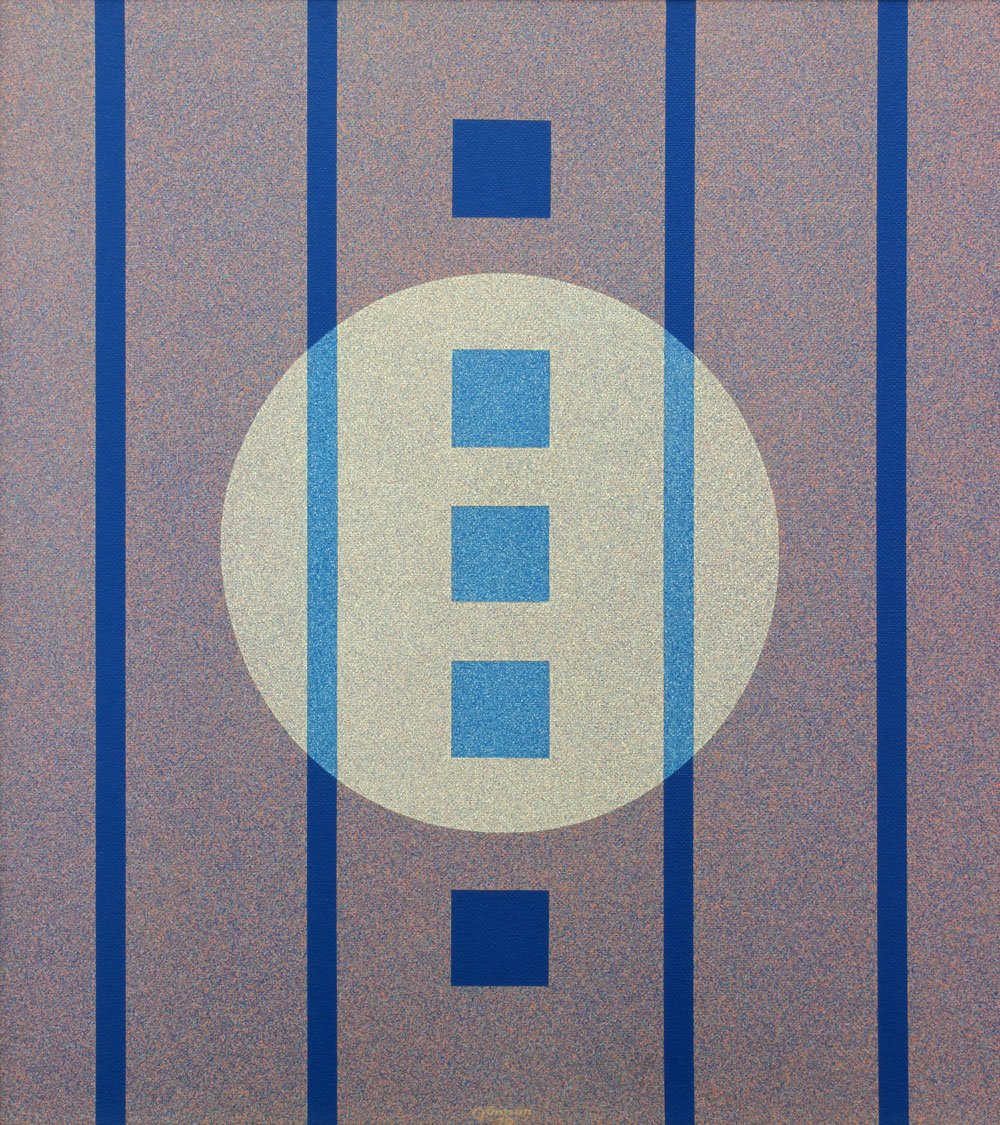

It was during this time that Jonson painted his first truly nonobjective paintings. His works from 1929-1937 are categorized as abstract because they begin with a symbol or form found in everyday life and abstract it into its primary shape (e.g. painting a mountain as a triangle or the sun as a circle). In fact, letters and numbers are the most basic form of abstraction that exist in human thought. The number “2” does not have any visual reference for the concept of two. It is a symbol that refers to the idea of two things. The same is true in the English language. The word “tree” does not visually reference a tree; it is a collection of symbols that English speakers acknowledge refers to the concept of a tree. Truly nonobjective painting does not begin with any acknowledged symbol or reference in reality; it strives to capture pure form and color totally separate from physical reality: “Cannot a totally nonrepresentational art be a stronger affair, a richer organization, than the assemblage of a great deal of material which is related to nature rather than to painting?” (Garman 87). Many artists never make this transition; it took Jonson decades to make this conceptual leap. Knowing that there was a general confusion between the terms abstract and nonobjective, Jonson adopted the term Absolute (also used by Kandinsky and Hilla Rebay) to describe these pieces. Most critics believe that his greatest achievement in Absolute art was between 1938 and 1949; however, he created many of his most profound works after 1960 (Hartel 304).

The defining event that separates Jonson’s Absolute period from his late period is the founding of the Jonson gallery in 1950. Jonson maintained his position at the University of New Mexico from 1934 to 1954, retiring as a full professor with a pension and professional honors. This connection with the university is in large part what enabled his dedication to creative explorations in painting rather than the commercial aspect of selling work. In 1948, he proposed the idea of founding the Jonson Gallery on the UNM campus to the board of regents. That year the project was approved and they began planning. He and John Gaw Meem designed it to serve as a living space, studio, and exhibition space for his work and other artists who shared his dedication to spiritual nonobjective art. The Jonson Gallery opened in 1950; this enabled Jonson to have an extremely productive late career (Hartel 372-373).

His late works differ from his Absolute period in a few fundamental aspects. In the mid-1950s, he began working on a much larger scale. Rather than painting on an easel as he had previously, he placed his canvas or Masonite on the floor. This allowed him to work from every angle and balance his pieces in new ways. In 1957, he adopted acrylic paint. This medium became a perfect fusion of his airbrushed watercolor paintings and his brushed oils. Oil paint does not work in most airbrushes due to its high viscosity; watercolor is suitable for airbrushing but lacks the depth of color and opacity achievable with oil—acrylic paints dry quicker than oil, work in an airbrush, and have a range and depth of color unattainable in watercolor. By 1961, he gave up on all other media and used acrylic paints exclusively—these works are referred to as Polymers. Jonson’s works from the 1950s stand as a transition period during which he relearned to paint using this new material and explored new artistic directions. The early 1960s show a rejuvenated expression and convey his spiritual vision in new and exciting ways (Hartel 370, 379).

During this late phase he worked extensively to support younger-emerging artists. Among these were Richard Diebenkorn, Agnes Martin, and the members of the Taos Moderns group. When Richard Diebenkorn attended UNM for his Master’s in Art, he had already taught at the California School of Fine Art and shown his work in several exhibitions. At UNM he chose to keep to himself and didn’t always submit to the will of his instructors. When the time came for him to graduate, his instructors wanted to fail him. Jonson, recognizing his talent as an artist, stepped in and threatened to bring the issue to the board of regents if his instructors failed him. Because of this intervention, Diebenkorn graduated from UNM in 1952 (Ware interview). In the 1960s, Jonson organized a traveling exhibition of the artists that he felt were the center of the Taos painters. They were dubbed “Group 7” and they consisted of Louis Catusco, Rini Templeton, Louis Ribak, Beatrice Mandelman, Wesley Rusnell, Oli Sihvonen, and John De Puy. In a letter to the author, John De Puy recalled Jonson:

Raymond Jonson was both a mentor and teacher. His concept of the spiritual in art has been a lifelong search—that I hope is reflected in my art. He helped organize—together with Dorothy Morang (senior curator of the State Museum of Art in Santa Fe) the first major exhibit of the Taos Modernists in the early ‘60s. He also inspired the founding of “Group 7” a group of modernists that he felt were the nucleus of the Taos group. It showed first at his gallery—then traveled nationally. He was almost a father figure to me – with advice – and material help during hard times (De Puy).

Jonson’s wife Vera passed away in 1965 after several years of declining health. Since they had no children, Jonson dedicated the last seventeen years of his life to painting and running the Jonson Gallery. In 1978, Jonson abruptly quit painting. The primary reason for this decision was his belief that an artist should retire at the apex of his creative work. In his catalog of works, he listed his final painting, Polymer No. 19, 1978, as Swan Song. Jonson spent the last four years of his life maintaining the Jonson Gallery and passed away in 1982 (Hartel 404).

Jonson’s career was not that of a celebrity artist, but a man dedicated to a singular vision which he pursued indefatigably, often to the detriment of his financial success. He could have painted more landscapes or continued as a stage designer, but he believed that his purpose in life was to paint spiritual-nonobjective art. In this, he faced many obstacles, but eventually he created an environment for this art to prosper beyond his own artistic vision. Jonson was a great artist, but it was his efforts as an innovator, teacher, curator, and mentor that truly defined him.

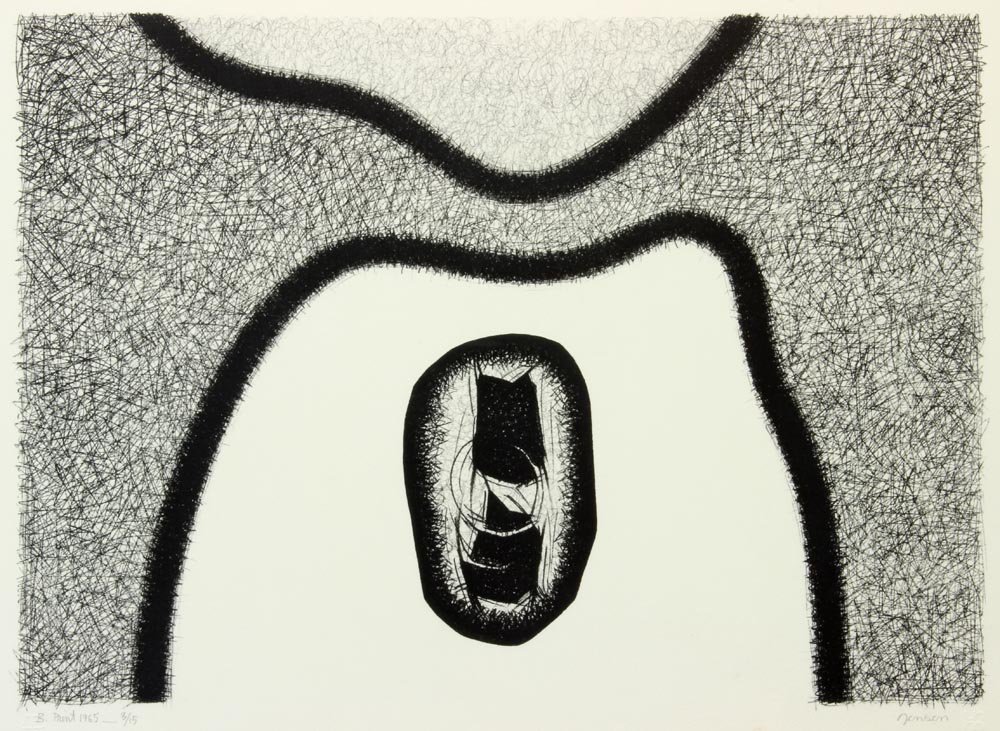

1943

Watercolor on board

30 x 22 inches

Signed, dated and tilted, verso

INQUIRE